Greetings again, good readers! It’s time for the next entry in my ever-lengthening series on creatures that have been described as “living fossils”, despite that this term isn’t terribly accurate literally, figuratively and in implication. Initially I was going to post about reptiles, amphibians and some fish today, but I instead decided to veer off towards mammals. Do not worry, these beasties’ time will come.

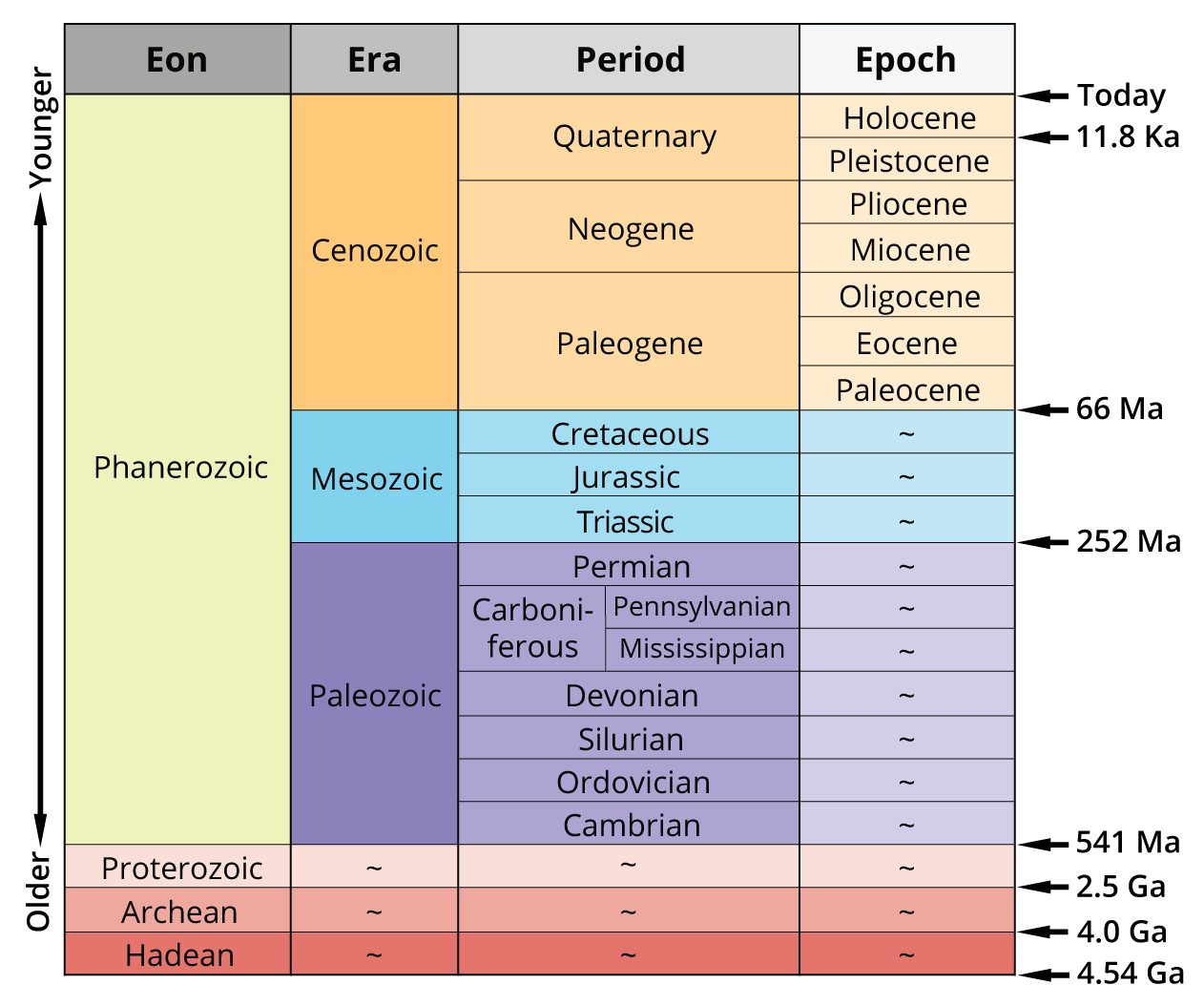

Despite mammals’ overwhelming popularity in terms of the Charismatic Fauna Olympics, they’re not as well-represented in the various lists of living fossils that are floating around, perhaps because they are by and large an evolutionarily “younger” group than say, fish or reptiles, or perhaps because the average person isn’t trained to necessarily identify what features in mammals are basal re: mammal evolution. Need an accessible primer on mammal evolution? National Geographic will help us today.

Alternatively, some of these animals are so obscure in the popular imagination (or are simply rare) as to make finding reliable information on them difficult. For example, consider the shrew-like venomous solenodon:

I very much want to bring you accurate, hard-hitting information on this odd little fellow, but it’s hard to find much beyond people waxing on its living fossilness,repeated declarations of extinction and rediscovery of living examples on both Hispaniola (the island shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and Cuba, the fact that it’s a venomous mammal that injects its venom through grooved teeth (like a snake), how rarely it is sighted, it’s awkward gait, and how endangered it is.

The case is the similar for many of these creatures, but I’ll do my best to inform in an entertaining fashion. In addition to the solenodon and the hastily-mentioned chevrotain, did you know that the star of the beginning of the alphabet, the insectivorous aardvark, is the last living species of its order (Tubulidentata)?

Despite some similarity in their appearance and even their popular names at times, aardvarks (meaning “earth pig” in Afrikaans), while they do eat ants, they are not anteaters, nor are they closely related to anteaters, which are native to South America (aardvarks are native to Africa).

In terms of relatives, aardvarks are more closely related to elephant shrews (which are not true shrews, naturally) and their kin. They belong to a fascinating clade called Afrotheria, which includes (among others) elephants, manatees and dugongs (the sirenians), tenrecs and another creature that I’ll address shortly, the rock hyrax.

Like echidnas, aardvarks suffer (?) from having a character be much more popular (and much more available in terms of works produced about them) than the actual creature. In this case, it’s Arthur the Aardvark from the Arthur series of books and PBS animation series, brainchild of Marc Tolon Brown. Still, it’s decent publicity, and by virtue of Arthur, aardvarks could be considered to have had some hand in the developing literacy of millions of children.

Next, we come to the hyraxes, the only living member of the order Hyracoidea. Despite their small size and their superficial resemblance to rodents, they are not rodents – hyraxes are just hyraxes, with their closest living kin being elephants, manatees and dugongs. Like the aardvark, the hyraxes also belong to clade Afrotheria and are the remaining members of a much more populous group.

Despite not being so famous in popular culture, hyraxes (also known as “dassies”) do have a bit of cachet in certain circles from being mentioned multiple times in the Old Testament of the Bible. Perhaps most famously, they are referred to in Proverbs 30:26:

…hyraxes are creatures of little power, yet they make their home in the crags…

There are several other mentions of hyraxes in the Bible as well, mostly in reference to dietary laws. If you look up the above verse from Proverbs using a web tool that displays multiple translations, you soon find that hyraxes are also referred to as “rock badgers”, “conies”, “rabbits”, or as non-rock “badgers” in the Bible. Additionally, some of the verses regarding the dietary cleanliness of hyraxes as a food source indicate that they chew the cud (and do not have split hooves), which they do not in fact do, as they are not ruminants.

This is a translation error – early translators of the Bible into English were not knowledgeable about Middle Eastern fauna and thus shoehorned the Hebrew terms for this animal or animals like it into animals that they were familiar with. If you have any interest in Biblical translation history and challenges, you will know this is not the first time this has happened.

As for cud chewing, it has been suggested that perhaps the writers were describing the hyrax in the act of chewing (which it does do, it is not a snake) and mistook its mastication for the act of cud-chewing.

In the modern time, hyraxes still live in the lands where the action of the Bible takes, and in fact are contributing to climate research by virtue of their habits of urinating in the same place every day (a site called a “midden”). In some locations, local hyrax colonies have been doing this for tens of thousands of years, creating a record of climatological data that can be derived from the contents of their urine.

According to this news piece from 2011, these adorable rock-dwellers have also been nuisances to their urban human neighbors in some locations. Can humans and hyraxes live together in harmony? STAY TUNED.

While there are other creatures to discuss (in particular, the Amami rabbit and the Laotian rock rat, both of which are visually distinct among their relatives), I’ll devote this last section to a mammal that is charismatic even among other charismatic mammals: the red panda (Ailurus fulgens).

Despite sharing a name with much-larger giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), red pandas are not bears, foxes, cats, raccoons, otters, dogs, or anything else that they may share visual traits with (pointed ears, ringed tail, etc).

Like a number of other creatures I’ve discussed, they existed in an ever-changing state of taxonomic limbo for quite a while; at one point, this limbo involved theorizing that they were related to the giant panda and other bears. Currently the red panda (and its extinct brethren) is the sole living member of family Ailuridae, which is itself part of the superfamily Musteloidea; members of this superfamily are called “musteloids”. Other members of Musteloidea include skunks, raccoons and weasels.

So how is a red panda like a giant panda? Well, they both live in China, though red pandas’ range stretches across the Himalayas; giant pandas are restricted to Sichuan, Shaanxi and Gansu provinces (more information on giant pandas’ current and historical ranges can be found here); both have bamboo-dependent diets (though red pandas enjoy a more varied diet than giant pandas); and they both have modified wrist bones that function as a sixth finger. Unfortunately, both have spots on the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List, with red pandas listed as “endangered” and giant pandas listed as “vulnerable”.

So which panda was called a panda (in English) first? According to linguist Susan Harvey, it was the red panda. Giant pandas came to be called pandas (in English) because of the mistaken belief that they were related to red pandas that seems to have surfaced in the early 1900s. Prior to their association with the red panda, giant pandas were called “parti-colored bears” or “mottled bears”. The word “panda” itself in English is thought to be of Nepali extraction, via French.

Because I seem to be linking these creatures with popular culture relatively often, red pandas recently acquired their own popular character in the form of Sanrio’s (the makers of Hello Kitty) Aggretsuko the Red Panda, who had an animation series of her own released on Netflix in April 2018.

And that concludes this portion of today’s presentation! Unfortunately, my attempts to compile a reasonably-fleshed out reading list for this entry turned out a bit meager. Regardless, please take a look at the below offerings and consider them for your future reading choices:

Arthur’s Nose (An Arthur Adventure), by Marc Brown.

Since I mentioned the Arthur books, I figured I should provide a little bit of attention to the book series. Those of you who are more familiar with Arthur’s more recent incarnations will notice that our friend has gone through some character design changes since the first book was released in 1976. As of August 2018, there are 45 books in the Arthur Adventure series, along with a number of spin-off series for different reading levels (easy readers, chapter books and audio books).

Aard-vark to Axolotl: Pictures from my Grandfather’s Dictionary, by Karen Donovan

Aard-vark to Axolotl, an eclectic series of tiny essays, is a collection of prose poems disguised as imaginary definitions, and a collaboration of text + image based on a set of illustrations from an old dictionary. Sometimes sneaky mysterious, sometimes downright weird, these small stories work on the reader like alternative definitions for items drawn from a cabinet of curiosities.

If you’re interested in checking out this item, please speak to a librarian.

Red Panda: Biology and Conservation of the First Panda, edited by Angela R. Glatston

Red Panda: Biology and Conservation of the First Panda provides a broad-based overview of the biology of the red panda, Ailurus fulgens. A carnivore that feeds almost entirely on vegetable material and is colored chestnut red, chocolate brown and cream rather than the expected black and white. This book gathers all the information that is available on the red panda both from the field and captivity as well as from cultural aspects, and attempts to answer that most fundamental of questions, “What is a red panda?” Scientists have long focused on the red panda’s controversial taxonomy. Is it in fact an Old World procyonid, a very strange bear or simply a panda? All of these hypotheses are addressed in an attempt to classify a unique species and provide an in-depth look at the scientific and conservation-based issues urgently facing the red panda today.

Red Panda not only presents an overview of the current state of our knowledge about this intriguing species but it is also intended to bring the red panda out of obscurity and into the spotlight of public attention.

- Wide-ranging account of the red panda (Ailurus fulgens) covers all the information that is available on this species both in and ex situ

- Discusses the status of the species in the wild, examines how human activities impact on their habitat, and develops projections to translate this in terms of overall panda numbers

- Reports on status in the wild, looks at conservation issues and considers the future of this unique species

- Includes contributions from long-standing red panda experts as well as those specializing in fields involving cutting-edge red panda research.

If you’re interested in checking out this item, please speak to a librarian.

While not technically about platypuses, it mentions platypuses in the title so I’m going to count it. Everyone likes accessible philosophy texts, right?

Outrageously funny, Plato and a Platypus Walk into a Bar… has been a breakout bestseller ever since authors—and born vaudevillians—Thomas Cathcart and Daniel Klein did their schtick on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Lively, original, and powerfully informative, Plato and a Platypus Walk Into a Bar… is a not-so-reverent crash course through the great philosophical thinkers and traditions, from Existentialism (What do Hegel and Bette Midler have in common?) to Logic (Sherlock Holmes never deduced anything). Philosophy 101 for those who like to take the heavy stuff lightly, this is a joy to read—and finally, it all makes sense!

Cathcart and Klein are clearly fond of putting creatures described as “living fossils” in the titles of their books. If you enjoyed their philosophy text, why not branch out to political rhetoric via philosophy and humor?

Thomas Cathcart and Daniel Klein, authors of the national bestseller Plato and a Platypus Walk into a Bar, aren’t falling for any election year claptrap—and they don’t want their readers to either! In Aristotle and an Aardvark Go to Washington, our two favorite philosopher-comedians return just in time to save us from the double-speak, flim-flam, and alternate reality of politics in America.

Deploying jokes and cartoon as well as the occasional insight from Aristotle and his peers, Cathcart and Klein explain what politicos are up to when they state: “The absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence.” (Donald Rumsfeld), “It depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.” (Bill Clinton), or even, “We hold these truths to be self-evident…” (Thomas Jefferson, et al).

Drawing from the pronouncements of everyone from Caesar to Condoleeza Rice, Genghis Kahn to Hillary Clinton, and Adolf Hitler to Al Sharpton. Cathcart and Klein help us learn to identify tricks such as “The Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy” (non causa pro causa) and the “The Fallacy Fallacy” (argumentum and logicam). Aristotle and an Aardvark is for anyone who ever felt like the politicos and pundits were speaking Greek. At least Cathcart and Klein provide the Latin name for it (raudatio publica)!

Until next time, dear readers! As always, feel free to comment if you find any of the entries here at the Free-for-All particularly edifying, wish to share your thoughts and suggestions, or find that any information I’ve presented is incorrect. Constructive feedback is welcomed!