Good day dear readers! I hope you enjoyed our last foray into the world of sharks, rays, skates, guitarfish and kin! Today we’re aiming a bit more broadly – an introduction to some examples of what are popularly called “living fossils”.

As with any category, the first questions to be answered include: “What is it? What belongs? What doesn’t belong? Why?” Unfortunately, these answers vary depending on who is answering the question. In their 1984 book Living Fossils, Niles Eldredge and S.M. Stanley defined living fossils as:

- Members of taxa (the plural of taxon, meaning a taxonomic group of any rank, such as a species, family, or class) that exhibit notable longevity in the sense that they have remained recognisable in the fossil record over unusually long periods;

- Show little morphological divergence, whether from early members of the lineage, or among extant species, and

- tend to have little taxonomic diversity

However, the term “living fossil” is now being questioned: is it time for the term coined by Darwin in his On the Origin of Species to be retired?

One of my favorite popular science writers, Ed Yong (author of 2016’s acclaimed I Contain Multitudes), argues that it should be abandoned on the basis that it implies that these organisms are in fact unchanged, when in actuality they show diversity and change over time apace with species not considered “living fossils”. That is, much of their living fossilness is based more on them having conservative body plans (looking “ancient”) rather than them actually lacking diversity or not exhibiting change over time.

In that case, what to call them? For purposes of this series of entries, I’m going to use the term “ancient organisms/creatures”. Whereas my previous entries dealt more with narrower classes of things, this one is a non-comprehensive tour of some organisms that have been described as members of this group.

Ancient organisms span the full gamut of organisms: bacteria, plants, animals, insects, fish, even creatures that perhaps aren’t always thought of as animals, like sponges.

While my space here is limited, I’ll do my best to give you a whirlwind introduction to these fascinating critters by type. First up:

BACTERIA: Stromatolites

Normally one thinks of bacteria more in terms of things you attempt to remove from your hands with soap at a sink, but our representative of bacteria, stromatolites, are incredibly cool. Here is why:

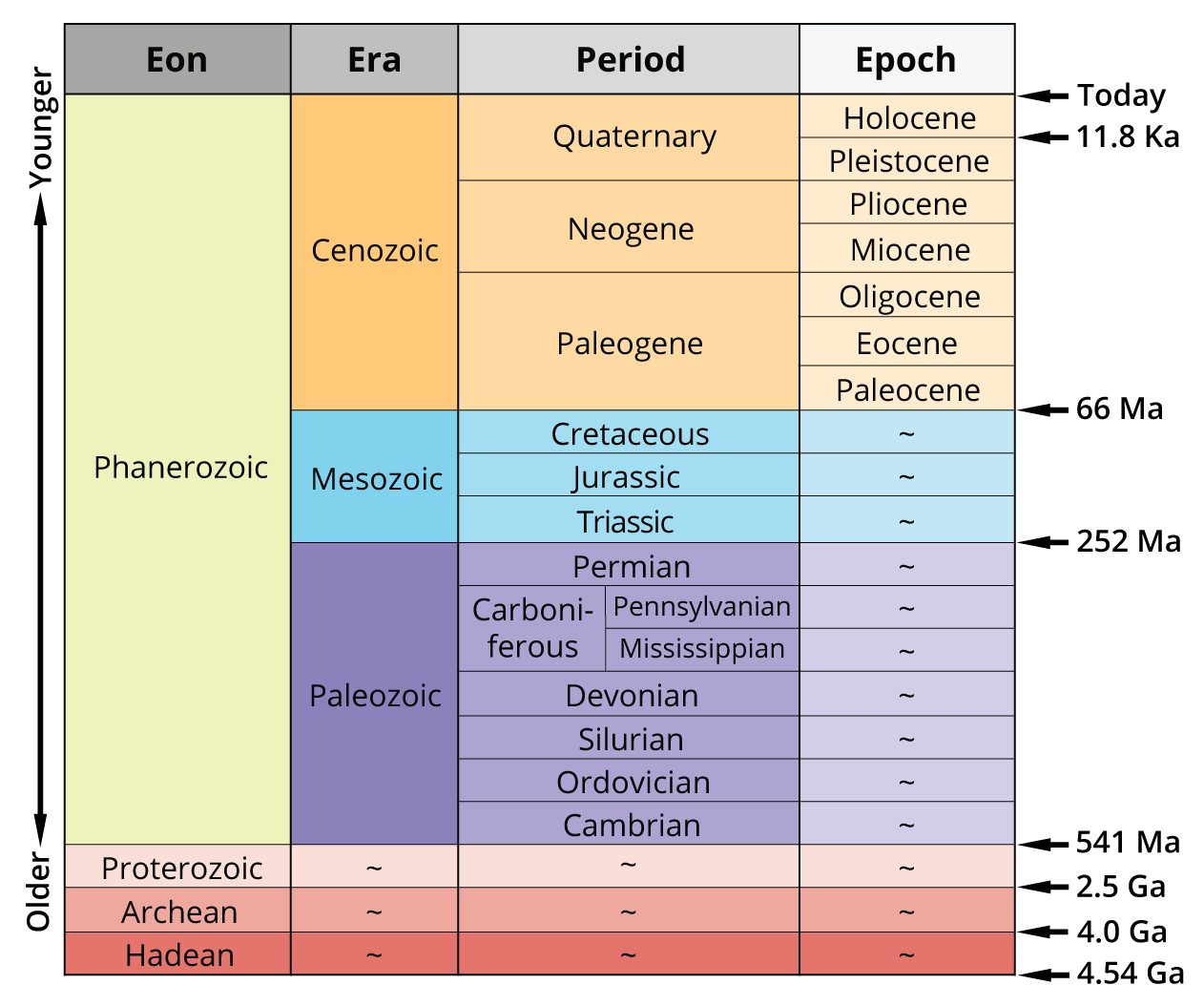

Stromatolites themselves are structures created by cyanobacteria (called blue-green bacteria or blue-green algae) accreting layers and layers of oxygen-producing microbial laminae (they’re photosynthetic) that then trap sediments, resulting in lithification over time; that is, they turn into stone. This may not sound especially scintillating until you realize how old these structures are – stromatolite fossils date back to the Archean eon. Here’s a geologic time chart for reference:

Excluding the Ediacaran fauna (who really deserve your attention because ancient stuff is wonderful), stromatolite fossils are the oldest evidence of life on Earth that we have. The fact that some of these organisms are still alive and metaphorically kicking is astounding. Their range (like that of so many things) was much wider in the past, to the point that many of their fossils are no longer accessible to humans due to plate subduction, a process that moves at a geologic pace.

This site has diagrams about where in the United States you can observe stromatolite fossils, which implies very old areas of exposed rock (which means FOSSILS! Bring your tools!). Even if they’re just sitting there eating light + air and defecating rock, stromatolites are venerable communities indeed. Here’s what they look like in fossil form, vertically sliced:

PLANTS: Cycads (Cycadales)

Moving on to plants, I am pleased to present to you these representatives: the cycads (depicted above), dawn redwoods/sequoias, the ginkgos, and welwitschia, which is a fun word to say.

Cycads are stout, squat, cone-bearing (but they’re not conifers) woody tree-like plants – however, unlike trees, they contain very little wood in their bark. Actually, they differ from most “modern” plants in most regards. Cycads look like many things, but their fossil evidence demonstrates their existence back to the Permian period (check the chart!), predating the dinosaurs.

Because of their striking appearance and appeal to collectors, many species of cycad are endangered or threatened. However, if you want to see cycads in person, may I suggest the Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden in Coral Gables, Florida? Currently, there are ~300 extant species of cycad; if you want to know the nitty-gritty about their taxonomy, The Cycad Pages and The Cycad Society are happy to oblige.

HOT GEOLOGICALLY-RECENT CYCAD NEWS: This study published in Science in 2011 (here’s a link to a more reader-friendly interpretation) provides another example of why the term “living fossil” may lead to incorrect assumptions – today’s cycads are not the exact same as cycads that lived during the age of the dinosaurs. However, that doesn’t mean that they’re not an ancient lineage.

The Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides)

The dawn redwood (native to Hubei Province in China) is the shortest of the trees that we refer to as redwoods (also known as sequoias), the most spectacular being the giant redwoods of California. Dawn redwoods are well-represented at various locations in the fossil record; however, their status as living fossils echoes that of the coelacanth: it is an organism that was thought to be extinct until it was discovered to still be living in the mid-20th century.

It now enjoys (?) its status as a popular tree to use in bonsai. Three dawn redwoods grow in Strawberry Fields, an area of New York City’s Central Park that serves as a tribute to John Lennon.

Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba)

Next, we have the distinctive ginkgo (also known as the maidenhair tree), known for its exquisite colors (they turn brilliant golden in the autumn), unique (sometimes) bifurcated-fan-shaped leaves, perceived value as a nutritional supplement, use in traditional medicine, and as a food source (the seeds). They are also apparently famous for the foul smell of their fallen leaves and berries.

Fossils related to the modern Ginkgo appeared during the Permian period; fossils that clearly belong to the genus Ginkgo appeared during the Jurassic period.

Unlike the other plants I’ve described here, Ginkgo are pleasantly unendangered – they’re popular ornamental plants, particularly due to their extreme hardiness in urban environments. Some ginkgo trees even managed to survive the dropping of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945 . Here is a New York Times op-ed from 2017 about conservation and the Hiroshima ginkgos. For further ginkgo edification, have a listen to this episode of the Generation Anthropocene podcast, talking about the tree and how humans have had a hand in its evolution and propagation.

Welwitschia (Welwitschia mirabilis)

The final ancient organism that I’ll talk about today is the weird-looking and appropriately-named Welwitschia mirabilis. In the image below, you’re looking at a healthy welwitschia – yes, this is how they’re supposed to look.

Welwitschia are odd plants native to Angola and Namibia in Africa, alone in their taxonomy. I’d write and describe them, but many other people have done so more completely and accurately than I am able to at length. In addition to having the longest-lived leaves in the plant kingdom, welwitschia appear in the fossil record in the Jurassic. Individual specimens are extremely long-lived, with reports of variable veracity aging them at 1,000-2,000 years.

While I haven’t mentioned it yet, welwitschia are a type of plant called a gymnosperm, distinguished by their unencased seeds. The only other currently-living gymnosperms include the conifers (pines, cypresses & others – this includes the dawn redwoods), cycads and ginkgos – doesn’t that wrap up neatly now?

While it is native to areas that are now arid, welwitschia is also grown and sought-after by botanical gardens. It’s a protected species, but most trade involves its seeds, rather than wholesale moving of the plant itself.

While I don’t have a close-up image of it offhand, a bit of trivia is that along with 52 other plants, welwitschia was embroidered into Meghan Markle’s 5-meter long wedding veil. Her veil featured the distinctive flora from each of the 53 Commonwealth countries, with welwitschia representing Namibia.

If you’re interested in making the acquaintance of welwitschia and don’t feel like going to Namibia or Angola, they can be seen at various botanical gardens, including the Chicago Botanic Gardens and The Domes in Milwaukee.

As seems to be my custom, I’ve spoken for too long and this is going to end up as multiple entries. I hope you look forward them, dear readers! In the meantime, have some reading recommendations so you can dive deeper into these august organisms and their stories:

Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses, by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

Living at the limits of our ordinary perception, mosses are a common but largely unnoticed element of the natural world. Gathering Moss is a beautifully written mix of science and personal reflection that invites readers to explore and learn from the elegantly simple lives of mosses.

Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book is not an identification guide, nor is it a scientific treatise. Rather, it is a series of linked personal essays that will lead general readers and scientists alike to an understanding of how mosses live and how their lives are intertwined with the lives of countless other beings, from salmon and hummingbirds to redwoods and rednecks. Kimmerer clearly and artfully explains the biology of mosses, while at the same time reflecting on what these fascinating organisms have to teach us.

Drawing on her diverse experiences as a scientist, mother, teacher, and writer of Native American heritage, Kimmerer explains the stories of mosses in scientific terms as well as in the framework of indigenous ways of knowing. In her book, the natural history and cultural relationships of mosses become a powerful metaphor for ways of living in the world.

The Oldest Living Things in the World, by Rachel Sussman

The Oldest Living Things in the World is an epic journey through time and space. Over the past decade, artist Rachel Sussman has researched, worked with biologists, and traveled the world to photograph continuously living organisms that are 2,000 years old and older. Spanning from Antarctica to Greenland, the Mojave Desert to the Australian Outback, the result is a stunning and unique visual collection of ancient organisms unlike anything that has been created in the arts or sciences before, insightfully and accessibly narrated by Sussman along the way.

Her work is both timeless and timely, and spans disciplines, continents, and millennia. It is underscored by an innate environmentalism and driven by Sussman’s relentless curiosity. She begins at “year zero,” and looks back from there, photographing the past in the present. These ancient individuals live on every continent and range from Greenlandic lichens that grow only one centimeter a century, to unique desert shrubs in Africa and South America, a predatory fungus in Oregon, Caribbean brain coral, to an 80,000-year-old colony of aspen in Utah. Sussman journeyed to Antarctica to photograph 5,500-year-old moss; Australia for stromatolites, primeval organisms tied to the oxygenation of the planet and the beginnings of life on Earth; and to Tasmania to capture a 43,600-year-old self-propagating shrub that’s the last individual of its kind. Her portraits reveal the living history of our planet—and what we stand to lose in the future. These ancient survivors have weathered millennia in some of the world’s most extreme environments, yet climate change and human encroachment have put many of them in danger. Two of her subjects have already met with untimely deaths by human hands.

Alongside the photographs, Sussman relays fascinating – and sometimes harrowing – tales of her global adventures tracking down her subjects and shares insights from the scientists who research them. The oldest living things in the world are a record and celebration of the past, a call to action in the present, and a barometer of our future.

Perhaps the world’s most distinctive tree, ginkgo has remained stubbornly unchanged for more than two hundred million years. A living link to the age of dinosaurs, it survived the great ice ages as a relic in China, but it earned its reprieve when people first found it useful about a thousand years ago. Today ginkgo is beloved for the elegance of its leaves, prized for its edible nuts, and revered for its longevity. This engaging book tells the rich and engaging story of a tree that people saved from extinction–a story that offers hope for other botanical biographies that are still being written. Inspired by the historic ginkgo that has thrived in London’s Kew Gardens since the 1760s, renowned botanist Peter Crane explores the history of the ginkgo from its mysterious origin through its proliferation, drastic decline, and ultimate resurgence. Crane also highlights the cultural and social significance of the ginkgo: its medicinal and nutritional uses, its power as a source of artistic and religious inspiration, and its importance as one of the world’s most popular street trees. Readers of this book will be drawn to the nearest ginkgo, where they can experience firsthand the timeless beauty of the oldest tree on Earth.

An enthralling detective story about evolution and natural history, and the botanical find of the century: the freak survival of a species that offers a window on to an ecosystem one hundred million years old. The discovery has been described as “the equivalent of finding a small dinosaur still alive on Earth.”

Cycads of the World: Ancient Plants in Today’s Landscape, Second Edition, by David L. Jones

Cycads superficially resemble palms and are often misidentified as such. However, cycads are actually a unique assemblage of primitive plants that have been around for at least 250 million years. They have become highly sought after for gardens, both private and public, and their present status as endangered plants has engendered an upsurge of interest in their conservation. With Cycads of the World, David Jones has achieved that difficult task of writing a scientifically accurate text, which is both easy to read and to understand.

For this second edition David Jones has added information covering over 100 new species and subspecies of cycads, and updated his material on the 200 species from the first edition. Each entry includes a full description, distribution and habitat information, and a detailed cultivation and propagation guide. Over 360 color photographs plus many other illustrations and maps facilitate easy identification for all living species. This second edition of Cycads of the World makes a fine addition to the library of anyone interested in exotic plants, including gardeners, landscape architects, horticulturalists, botanists, and the curious reader alike.

Every rock is a tangible trace of the earth’s past. The Story of the Earth in 25 Rocks tells the fascinating stories behind the discoveries that shook the foundations of geology. In twenty-five chapters―each about a particular rock, outcrop, or geologic phenomenon―Donald R. Prothero recounts the scientific detective work that shaped our understanding of geology, from the unearthing of exemplary specimens to tectonic shifts in how we view the inner workings of our planet.

Prothero follows in the footsteps of the scientists who asked―and answered―geology’s biggest questions: How do we know how old the earth is? What happened to the supercontinent Pangea? How did ocean rocks end up at the top of Mount Everest? What can we learn about our planet from meteorites and moon rocks? He answers these questions through expertly chosen case studies, such as Pliny the Younger’s firsthand account of the eruption of Vesuvius; the granite outcrops that led a Scottish scientist to theorize that the landscapes he witnessed were far older than Noah’s Flood; the salt and gypsum deposits under the Mediterranean Sea that indicate that it was once a desert; and how trying to date the age of meteorites revealed the dangers of lead poisoning. Each of these breakthroughs filled in a piece of the greater puzzle that is the earth, with scientific discoveries dovetailing with each other to offer an increasingly coherent image of the geologic past. Summarizing a wealth of information in an entertaining, approachable style, The Story of the Earth in 25 Rocks is essential reading for the armchair geologist, the rock hound, and all who are curious about the earth beneath their feet.

Stromatolites, by Ken McNamara.

Lastly, if you have access to online materials via Endicott College, Gordon College, Salem State University or Phillips Academy, then you have electronic access to Ken McNamara’s Stromatolites!

David Attenborough began his extraordinary TV series, The Living Planet at Shark Bay in Australia’s northwest, because crossing the low dunes and descending to the beach is like slipping billions of years back in time. Where the waves gently break on the shore are stromatolites, rising like rows of concrete cauliflowers from the ocean. While they may look like inanimate rocks, examining a piece from the surface under a powerful microscope shows that it is teeming with life. Stromatolites are complex domes or columns of sediment formed by microbiological communities.

Unbeknownst to many Australians, Shark Bay is home to one of the most excellent records of ancient life on earth, a stromatolite, which is literally a living fossil. Stromatolites exist in only a few places on earth, and are formed by the trapping, binding, and cementing of sedimentary grains by microscopic bacteria (or microbes). These “living rocks”, as they are sometimes called, teem with the very oldest life forms on earth, having remained virtually unchanged during the comings and goings of animals and plants. In his new book Stromatolites, Ken McNamara shows readers how these ancient formations are a window to the past.